Demystifying the component architecture

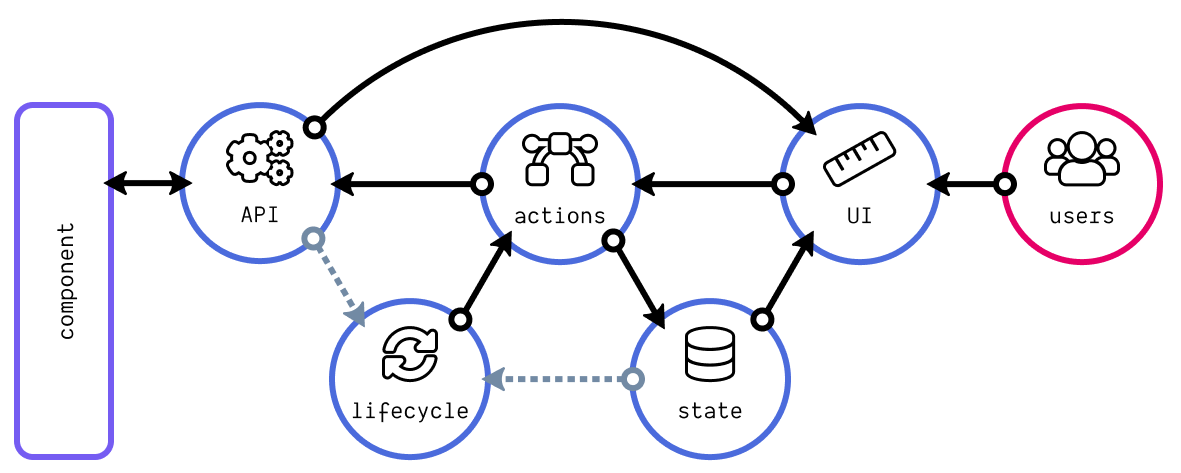

In complex applications, UI components consist of more building blocks than some state and UI. Before I already described a different way to look at our reusable UI components. We can look at them from developers' and users' perspectives at the same time. But on a conceptual level, components have more elements important to their behavior. It is important for developers to understand these concepts. Especially when working on big, complex and critical applications. By having an uniform way of looking at a component, we create the 'UI component anatomy'. Those familiar with the flux-pattern can this pattern coming back as well in the anatomy.

The API, also known as properties #

Interfaces are a way to describe how we want others to use and interact with our work, our components. The UI is a good example of an interface. It describes what we want our users to see and what we allow for interaction.

Interfaces are a way to describe how we want others to use and interact with our components

But what about the developers? The API of our components, better known as props or properties in most frameworks, is the interface for developers. There are some different API types we can define for other developers.

- Configuration: interfaces that allow developers to determine how our UI component should look and act. These are often static values that do not change based on user interaction. Examples are

classNameorusePortal; - Data: data often lives higher in the component tree. These interfaces allow data to be present and used in our component. These flows are uni-directional. An example is the

valueproperty; - Actions: sometimes we need to invoke changes higher in the component tree. This requires callback functions to pass through the API. An example is the

onChangeproperty.

To be in line with modern frameworks, I both use the terms props/properties and API

State #

State is a mutable object that dictates the behavior and UI of our component. It is often combined with data received through the API. In the example below, we have a modal component with an incorporated button. When clicking the button, we set the value of show to true. Now our modal becomes visible for the user.

function MyModal (props) {

const [show, setShow] = useState(false);

const handleShow = () => setShow((s) => !s);

return (

<>

<button onClick={handleShow}>...</button>

{show && <Modal onClose={handleShow}>...</Modal>

</>

);

}

The addition of a state to a component makes it sometimes easy to introduce bugs. The data and action properties are part of the 'data-flow'. But we often interrupt this with our state by copying values from the data properties into our state. But what happens if the values change? Does our state also change? Should it? Look at the example below look of what happens when showModal updates. If

MyComponent is already part of the component tree, then nothing happens. We have interrupted the data-flow. Don't.

function MyModal({ showModal }) {

const [show, setShow] = useState(showModal);

if (show) return null;

return <Modal onClose={handleShow}>...</Modal>;

}Actions #

As you can see in the diagram, actions link everything together. They are functions harboring small pieces logic. User interaction (e.g. a button click) trigger actions. But life-cycle methods, as described later, also trigger actions. Triggered actions can use data from the state and properties in their execution. Actions can come in many forms:

- Actions defined inside the component as a separate function;

- Actions defined in the life-cycle method of the component;

- actions defined outside the component and used in many components. Good examples are the actions within a module of the scalable architecture.

Below you can see part of a small React component example with two different actions. The first action changes the state on interaction (e.g. typing in an <input /> field). The second action triggers the changes. It removes the modal, it makes an external call to a server to save the values and resets the internal state.

function MyComponent(props) {

const [show, setShow] = useState(true);

const [state, setState] = useState();

const save = useMyApiCall(...);

function handleChange(value) {

setState((old) => ({ ...old, key: value });

}

function handleClose() {

setShow(false);

save(state);

setState();

}

return <>...</>;

}The above component has some small flaws, as does two different state updates in one action. But, it fits its purpose.

Lifecycle #

User inaction results in changes in the state of our component, or higher in the component tree. Data received through the API reflect these changes. When change happens, our component needs to update itself to reflect these changes. Or it needs to re-render. Sometimes, we want your component to execute extra logic when this happens. A so-called 'side-effect' needs to be triggered. of the changing values.

A simple example is a search component. When our user types, the state of the component should change, invoking a re-render. Every time we type, we want our component to perform an API-call. We can do this with the onChange handler of <input />. But what if our API-call depends on a value provided through the properties? And what if that value changes? We need to move our API-call to an update life-cycle method, as you can see below.

function SearchComponent({ query }) {

const [search, setSearch] = useState("");

useEffect(() => {

myApiCall({ ...query, search });

}, [query, search]);

const handleSearch = (e) => setSearch(e.target.value);

return <input value={search} onChange={handleSearch} />;

}Updates are not the only life-cycle methods. We also have the initialization of the component or the mounting of the component. Life-cycle methods trigger after rendering. This means that the initialization happens after the initial render. We have the life-cycle method for when a component is removed from the component tree. It is unmounted.

Most times, the logic called in life-cycles methods can be shared with other life-cycle methods or with handlers in the UI. This means we are invoking actions in our life-cycle methods. Actions, as illustrated, can cause changes in the state. But, life-cycle methods are called after state changes. Calling state-changing actions might cause a re-rendering loop. Be cautious with these types of actions.

The UI #

The UI describes what we want our users to interact with. These interactions, such as clicking on a button, trigger actions. It results from the rendering of our UI component. State changes or changing properties trigger the rendering. It is possible to trigger some 'side-effects' when this happens in the components' life-cycle methods.

It is often possible to add logic to our rendering. Examples are conditional visibility or showing a list of data with varying sizes. To do so, we need logic, rendering logic. This be something simple as using a boolean value from the state, or use an array.map() function. But sometimes we must combining many values in our rendering logic or even use functions to help us. In such a case, I would take that logic outside the rendering function itself as much as possible.

function MyModal ({ value }) {

const [show, setShow] = useState(false);

const showModal = show && value !== null;

return (

<>

<span>My component!</span>

{showModal && <Modal onClose={handleShow}>...</Modal>

</>

);

}Conclusion #

When building our components, we can use various building blocks that work together. On both ends, we have interfaces for different audiences. We allow developers to interact with our UI components and change their behavior. On the other side, we have users interacting with our components. Different elements inside a component link these two interfaces together. By using a uniform structure for our components with established patterns, we can create realiable and maintainable UIs.