In the beginning of 2022 I've updated this article with the sections 'Owls v.s. flex-boxes' and 'What about performance'.

It is not a secret that I love CSS. A few years ago I fell in love with a very simple, but powerful CSS selector. Back then I was expanding my CSS to the next level. I knew about the specificity and the cascade. I had no issue using CSS from scratch or with a framework. But I came across Heydon Pickering and later his 'lobotomized owl selector'. This selector blew my mind. At the CSS Day, he even showed another beauty, called the 'flexbox holy Albatros' (you can watch it here). These types of solutions showed me that solving solutions in CSS can be easy or elegant. So, Heydon, this one is (partly) for you.

The lobotomized owl selector #

Heydon explains the selector better in his article than I can. But I will provide a quick summary. The selector is, as mentioned, very simple: * + *. The * is the universal selector in CSS, it applies to all elements in the DOM. The + is the real hero of this piece of CSS code. It has the beautiful name of

'adjacent sibling combinator'. It applies the defined styles to the second element if immediately follows the first element. With our selector, it applies styles to all non-first elements on the same level in de DOM. Unless other rules have a higher specificity.

* + * {

...;

}

So why is this selector so powerful? I found the selector when searching for a spacing solution for a blogging website. I wanted to create enough space between paragraphs, but also to their parent element. Many solutions exist to solve this. You can give every element a margin-bottom. This has a side effect on the last element. To solve this, override the styles with the :last-of-type pseudo-selector. Another solution is to add both a padding-top and

padding-bottom to each paragraph. This can create unwanted side-effects with paddings of the parent element. More in-depth description of this specific problem and solution can be found on Every Layout, which is a brilliant website.

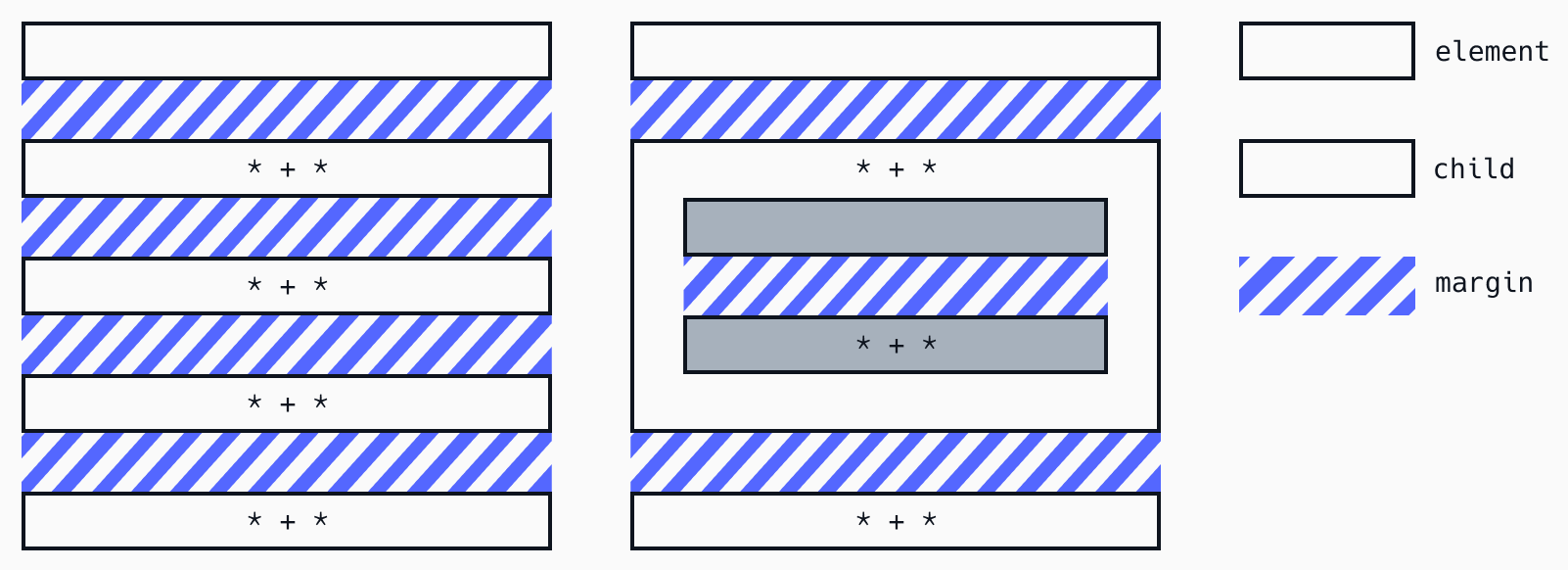

The * + * is an elegant solution when using margin-top. The margin-top is only applied between the elements.You know what makes it powerful? In this setup, it works on nested elements! As you can see below, the margin-top rule applies to every element in the list. On the right, the second element gets not only the styling rule, but it also has two child elements. Of those child elements, the second one also gets the margin.

These days most browsers also support logical operators, that are more considerate towards different users (e.g. left-to-right readers). Instead of using margin-top, you can use margin-block-start to be more inclusive.

Algorithms in UI #

The owl selector is a wonderful example showing how complex parsing CSS selectors can be. It shows the real power of CSS. Why? Because it works nested. In any programming language, this can become complex fast. The nested nature of the selector can is comparable to recursion. Before diving into the recursive solution, let's look at the pseudo-code for a flat list of elements. Now instead of pseudo-implementing

* + *, lets look at something like img + p. This means that in our implementation we need check the typing of the first and second element.

The below pseudo-code examples do not represent how browsers evaluate CSS selectors. They are just examples to show how the mental models apply in other languages.

function isFirst(item) { ... }

function isSecond(item) { ... }

function owl(list, apply) {

for (i = 1; i < list.length; i++) {

if (isFirst(list[i]) && isSecond(list[i - 1])) {

apply(list[i]);

}

}

}With the function, we can work with lists of varying types of elements and check if adjacent elements fit our criteria. We are only lacking the nesting capabilities of our CSS selector. In HTML any element can have children. This means that even our elements complying with our adjacent rule can have children. This means that we need to first execute apply, but afterwards call owl again, when the element has children.

function isFirst(item) { ... }

function isSecond(item) { ... }

function hasChildren(item) { ... }

function owl(list, apply) {

for (i = 1; i < list.length; i++) {

if (isFirst(list[i]) && isSecond(list[i - 1]))

apply(list[i]);

if (hasChildren(list[i]))

owl(list[i], apply);

}

}The above pseudo-code can become more complex if our CSS becomes more complex. We've only implemented a mental model now for the owl selector, and some variations. Try to combine it with different pseudo-selectors, or change its specificity. By doing so, you will see how powerful CSS has become.

Owls vs flex-boxes #

When you don't care for the recursive power of the owl selector, you might wonder: why not use flex-boxes with flex-gap. Like setting a flex-gap on the parent, the owl-selector sets the default gap between elements. The owl-selector makes things just a lot more adaptable. The owl-selector is used on this page to put a gap between elements of the article you are reading. But as you can see, the gap is not equal between all elements. Between a header and paragraph, there is

a much smaller gap!

.post h2 + p {

margin-top: 0;

}

By defining rules with a higher specificity compared to * + *, we can overwrite the default layout behavior we are seeing. The example above shows how the gap between a header and paragraph can be reduced. When trying to achieve the same effect with flex-gap, you have start working with (negative) margins on elements. You are now using two competing ways to determine relative positioning. This creates less stable code, more layout issues, and makes debugging layout issues

a lot more difficult.

What about performance #

Recursion sounds scary for most developers. The code looks efficient and small, but in reality it can cause a lot of performance issues. So what is the impact of a * + * selector on performance? And should I care? Well, the short answer is no. CSS is hardly the cause of performance issues. CSS animations out perform JavaScript animations.

Yes the * selector is a 'slow' CSS selector. If we look at the theoretical complexity, this would be a O(n). But what about * + *?. Well, as this selector just takes the next element, its theoretical complexity is O(n) as well! In reality, * + * is just a little but slower than a standalone *. So the owl selector performs almost equal to your

CSS reset on the box-sizing. In most cases even better, as most reset ::after and ::before on * as well.

For comparison, a * * has a theoretical complexity of O(n^2). This is because browsers evaluate CSS right-to-left. For the selector nav a we see a navigation with link in it. The browser sees a link within a navigation. This nuance has a big impact on performance. This is the reason why lengthy selectors have a

bad performance (and maintainability). And, the reason why * * has a complexity of O(n^2).

Again, performance is not an issue for CSS. But, there are simple ways to increase the performance of the owl selector. You can scope it (e.g. .post > * + *) or make it target more specific elements (e.g. p + p). The quality of your product will benefit more from clean, maintainable and less code. This results in less bugs, and smaller files that have to transferred via the users' network.

Wrapping up #

Almost everybody can apply simple CSS rules or styling rules. Solving more complex (or even easy) problems requires more in-depth knowledge. Knowledge of computer science concepts becomes important, as they are the result of several complex CSS rules. A simple CSS selector can mean that you apply a recursive function. The mental model of the result remains the same. You are applying algorithms to create a UI. This is exactly the reason I love CSS. Something simple can become a powerful UI manipulation tool.